Day 140 of Colourisation Project – September 24

Challenge: to publish daily a colourised photo that has some significance around the day of publication.

Every year in Melbourne, Australia, we have The Melbourne Cup, a horse race that literally stops a nation. It has run on the first Tuesday of November every year since 1875 [1] and it sees racing enthusiasts and socialites alike, flocking to Flemington Racecourse. In 1943 and 1944 Australia experienced a similar swell of frenzy among art enthusiasts (and socialites) when a portrait painting shifted the Second World War off the front pages of the nation’s newspapers. Not since the portrait of Dorian Gray has a painting caused such an almighty uproar!

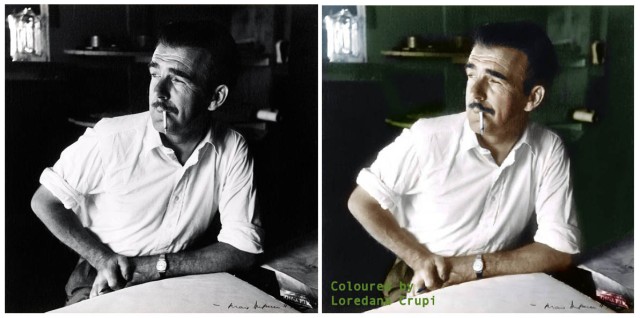

The artist in question was Sir William Dobell. Born this day, 24 September, 1899, Dobell was one of Australia’s most celebrated portrait and genre painters. Renowned for his unique style of painting, William Dobell was a household name in post-war Australia. However his name is forever associated with the infamous court case which followed his 1943 Archibald Prize for his stylised portrait of colleague and artist, Joshua Smith, in Portrait of an Artist (Joshua Smith).

Dobell cemented his reputation as one of Australia’s greatest artists by becoming the first artist to win both the Wynne Prize for landscapes and the Archibald Prize for portraiture in the same year. His incisive portraits earned him the Archibald Prize [2] for portraiture three times (1943, 1948 and 1959).

Although Dobell was highly regarded as an artist he was also the most controversial portrait painter of his generation. Dobell, who received a knighthood in 1966, was the quintessential Aussie bloke — more at home in his local pub with a bunch of mates than in the limelight of international stardom. When Portrait of an Artist (Joshua Smith) won the Archibald it unleashed a storm. Dobell found himself thrust into centre of one of Australia’s greatest art controversies, that would leave a deep scar on his creativity for some time.

Whilst the main attack was led by the conservatives of the Sydney art world, who dubbed his work a caricature, Dobell was deeply distressed when Joshua Smith’s parents turned up on his doorstep early one morning to try to suppress the painting.

His prize-winning portrait became the subject of a sensational legal case in 1944, when two unsuccessful entrants in the contest filed a lawsuit against him and the organisers of the award, challenging not only Dobell’s right to the prize, but the very idea of art itself. Dobell won the legal battle but his confidence in his art was destroyed. Australia’s household name was now a broken man.

The case was portrayed in the media as a victory for modern art over traditional art. But according to Dobell’s friend, Hal Missingham, this was not so. Missingham, a former director of the Art Gallery of NSW explained “Dobell was not, nor ever claimed to be, a modernist. He worked in the classical tradition, heavily influenced by Rembrandt, but his work at the time seemed innovative, and was thus labelled modern. The people who called Dobell’s work modern wouldn’t know modern art from a hole in the ground!”

After the ordeal which lasted almost two years and with his health affected, Dobell had little desire to paint. Humiliated by the publicity of the courtcase, Dobell sought refuge in Wangi Wangi, a small community just north of Sydney, far removed from the cut throat world of an antagonistic art scene fuelled by jealousy, conspiracy and scorn. In Wangi Wangi, he found community and friendship, and with time reclaimed his passion to paint. This time however he took up landscape painting.

His Archibald Prize split not only the art world asunder but people from all walks of life. Dobell was deluged with lucrative portrait commissions and many offers of support. One source of support came from the Daily Telegraph, then owned by Sir Frank Packer. “If William Dobell were a hack painter, he could win six Archibald Prizes without wringing one howl from the studio mediocrities. His crimes are: real talent and visual imagination.”

Former Prime Minister of Australia, Sir Robert Menzies, said at the time that he would be happy to be painted by Dobell, although later in 1960 when indeed Dobell painted his portrait, he found it so unflattering that he refused the gift of it from the publishers, Time Magazine.

As fellow artist, James Gleeson, comments in his 1964 biography, William Dobell,

“He sees the ordinary and paints it as though it was extraordinary; he sees the commonplace and paints it as though it was unique; he sees the ugly and paints it as though it was beautiful. It is a characteristic he shares with Rembrandt.

One of the astonishing things about Dobell’s portraiture is his ability to adjust his style to the nature of the personality he is portraying … If the character of his sitter is broad and generous, he paints broadly and generously. If the character is contained and inward looking, he uses brushstrokes that convey this fact. In his later portraits one has only to look at a few square inches of a painted sleeve to know what sort of person is wearing it.”

Renowned Australian artist, John Olsen, then an art student remembers singing stridently at parties to the tune of Champagne Charlie,

In 1958 the art world suffered immeasurably, when Dobell’s infamous portrait of Joshua Smith was burned in a fire at the home of its owner Sir Edward Hayward in Adelaide. Sadly the top half of the painting was destroyed. In 1969 Hayward had the painting restored by the conservator, Kenneth Malcolm. Although it was once again exhibited as the Dobell masterpiece, in reality it was a poor version of the original.

In 1948, Dobell won both the Archibald with his portrait of Margaret Olley and the Wynne prize for Storm approaching Wangi and eleven years later in 1959 Dobell won his third Archibald with a portrait of his physician, Dr E. G. MacMahon.

Between 1960 and 1963, he was commissioned by Time magazine to paint the first of four portraits for cover illustrations. These included those of Prime Minister Menzies, the President of South Vietnam, Ngo Dinh Diem, the chairman of General Motors Corporation, Frederick G. Donner and the Malaysian Prime Minister, Tunku Abdul Rahman.

Other notable portraits by Dobell include those of Thelma Clune, (1946) Margaret Olley (1948), Sir Charles Lloyd Jones (1951), Dame Mary Gilmore (1957), Camille Gheysens (1957), Sir Hudson Fysh (1950), Sir Leon Trout (1959), Helena Rubinstein (1963) and several self portraits.

Dobell died in 1970 in Wangi Wangi at the age of 71. The sole beneficiary of his estate was the Sir William Dobell Art Foundation, founded in 1971.

He was made an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) in 1965 and was knighted in 1966.

The federal electoral Division of Dobell in New South Wales is named after him.

________________________________________________________

“You might say I am trying to create something instead of copying something, when I set out to paint a portrait. To me, a sincere artist is not one who makes a faithful attempt to put on a canvas what is in front of him, but one who tries to create something which is a living thing in itself, regardless of the subject.” – William Dobell